1. Introduction

Dental implants are expected to transfer occlusal loads to the surrounding bone while maintaining mechanical stability of the implant–abutment–crown assembly. Conventional implants are primarily titanium-based, which offers high strength and corrosion resistance; however, titanium’s comparatively high stiffness may reduce mechanical stimulus in adjacent bone, contributing to stress/strain shielding concerns in some scenarios. A common design rationale for composites is therefore stiffness tailoring: by bringing implant/abutment stiffness closer to bone, load sharing can become more “physiological,” particularly in the crestal cortical region where overload or shielding signatures frequently concentrate.

Recent finite element investigations have explored hybrid Ti–PEEK implants explicitly as a strategy to address stiffness mismatch and its biomechanical consequences. In parallel, PEEK and fiber-reinforced PEEK variants are studied as metal alternatives for implants and/or abutments, aiming to modify peri-implant stress patterns while keeping component stresses within safe limits.

While many implant simulations report stresses (e.g., von Mises) and strains, energy-based metrics can add interpretability: they show where the mechanical work goes (implant vs cortical vs cancellous bone), how strongly the load is “routed” through the interface, and how composite architecture changes the distribution. This paper consolidates an energy-based framework for composite dental implant simulation, with particular emphasis on:

- Strain energy and strain energy density (SED) as descriptors of load transfer,

- Composite architecture effects (e.g., short vs continuous carbon-fiber reinforcement),

- Interface integrity (osseointegration assumptions and debonding/contact modeling),

- Trade-offs between stress reduction and deformation/fatigue sensitivity under oblique loading.

2. Energy-Based Metrics for Dental Implant Biomechanics

2.1 Strain energy and strain energy density (SED)

For a deformable body, the elastic strain energy

U reflects how much work is stored elastically under loading:![]()

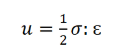

The strain energy density u is the local counterpart:

In implant biomechanics, SED can be interpreted as a practical proxy for the mechanical stimulus experienced by bone. When implant stiffness increases, the system may store more energy in the implant components and less in bone; when stiffness decreases, energy may be redistributed toward the peri-implant region—though not always uniformly. The practical value of energy reporting is that it can separate “bone is loaded” vs “bone is bypassed” patterns in a physically meaningful way.

2.2 Energy routing and composite stiffness

Composites affect energy routing primarily through:

Elastic Modulus: PEEK has lower stiffness than titanium and there is considerable variability in CFR-PEEK stiffness with respect to fiber fraction/orientation/continuity.

Anisotropic Properties: The stiffness of the CFR-PEEK composite will exhibit orthotropic properties when subjected to loads along the primary stiff axes of the composite.

Damping/Viscoelasticity (Optional): Polymeric matrices can dissipate energy; most dental finite element (FEA) analysis assume a linear elastic model; however, if necessary, this linear analysis can be extended to include viscoelasticity or time-dependent behavior.

A key insight from comparative studies is that “composite” is not a single category: short-fiber CFR-PEEK and continuous-fiber CFR-PEEK can produce different peri-implant patterns. For example, a 2024 FE study comparing different CFR-PEEK architectures reports that short-fiber CFR-PEEK produced more uniform stress distribution around bone–implant contact than titanium, and emphasized potential reduction of stress shielding/stress concentration signatures.

2.3 Interface integrity as an energy problem

Beyond bulk energy measures, implant success depends on bone–implant interface conditions:

Perfect bonding (often used as an idealized “full osseointegration” assumption),

Frictional contact (for early-stage or partial integration),

Debonding/contact evolution (more realistic).

A key limitation of many simplified FEA models is the assumption of perfect bonding everywhere. More realistic formulations have been proposed to capture debonding of partially osseointegrated interfaces using frictional contact laws calibrated to experiments. In an energy-based reporting mindset, interface integrity can be quantified by contact work, slip, separation tendencies, and micromotion thresholds rather than by stress alone.

3. Finite Element Workflow for Composite Dental Implant Evaluation

This section outlines a practical modeling route suitable for a thesis or an SCI-level paper comparing titanium vs composite concepts (PEEK/CFR-PEEK, Ti–PEEK).

3.1 Geometry and components

A typical model includes:

Implant fixture and abutment (optionally screw),

Crown (ceramic/metal–ceramic/composite),

Cortical and cancellous bone segments (mandible or maxilla, depending on scenario).

Mesh refinement is critical near:

Implant neck/crestal bone region,

Thread–bone contact zone,

Abutment–implant connection.

3.2 Material models

Titanium is commonly treated as linear elastic isotropic.

PEEK and reinforced PEEK can be modeled at different fidelity:

Linear elastic isotropic (baseline screening),

Orthotropic (recommended for CFR-PEEK),

Component-level variants (e.g., PEEK abutment on titanium implant) as a “system” design choice.

A 2024 3D FEA comparing titanium vs PEEK abutments explicitly highlights how substituting abutment material can change stress distribution in implant systems and supporting bone.

3.3 Loading: vertical vs oblique occlusion

Dental implants rarely experience purely axial forces; oblique loads often dominate peak responses. Multiple studies emphasize that oblique loading can elevate component stresses and alter bone loading patterns, making it a necessary scenario for composite evaluation. For CFR-PEEK vs titanium comparisons, oblique loading is also where stress–strain trade-offs become clearer.

Recommended load cases:

Axial (e.g., 100–200 N),

Oblique (e.g., 30°–45° with comparable magnitude),

Optional parafunctional/bruxism case for sensitivity.

3.4 Interface conditions and osseointegration

At minimum, compare:

Bonded interface (full osseointegration, best-case stability),

Frictional contact (early-stage or partial integration).

For higher realism, incorporate debonding/contact evolution. A frictional-contact formulation for debonding partially osseointegrated implants has been proposed and can be used to represent progressive loss of adhesion and tangential debonding.

3.5 Validation considerations

Where possible, FE predictions should be supported by experimental validation. A review focused on finite element contact analysis in dental/implant restorations notes the utility of surface strain measurement for validating FE models and highlights contact analysis as a critical technique.

4. Effect of Composite Materials in Dental Implant Systems

This section summarizes what composite substitution typically changes and how to report it using energy metrics.

4.1 Peri-implant bone: stress/SED redistribution (the “load-sharing” effect)

Ti–PEEK hybrids: A dedicated Ti–PEEK composite implant FEA compared multiple hybrid layouts and showed that hybrid concepts can modify the host bone mechanical response relative to conventional titanium, including scenarios with and without marginal bone loss. Interpreted through energy metrics, such designs can be evaluated by whether they increase SED/strain energy in peri-implant bone without creating localized overload.

PEEK / reinforced PEEK implants: Studies analyzing PEEK and reinforced PEEK implants report meaningful shifts in bone stresses and deformations relative to titanium. This is precisely where SED maps become useful: two designs may show similar peak stress yet different spatial SED patterns, indicating different remodeling stimuli distributions.

Reinforcement architecture matters: A 2024 FE comparison of different CFR-PEEK configurations (including short-fiber vs continuous-fiber reinforcement) reported that a short-fiber CFR-PEEK design produced more uniform stress distribution around the bone–implant region than titanium, with conclusions framed around reducing stress shielding/stress concentration tendencies.

4.2 Implant/abutment components: stress decreases can accompany strain increases

A 2025 CFR-PEEK vs titanium FEA reported that titanium implants can exhibit higher von Mises stresses in implant/abutment under oblique loading, while CFR-PEEK components can show reduced stress but significantly higher strain levels. The same study noted more uniform stress distribution in peri-implant bone for CFR-PEEK, suggesting potential reduction in stress shielding—yet raising concerns about deformation-driven risks and fatigue sensitivity.

Implication for energy reporting: do not only report peak von Mises. Pair it with:

SED maps in cortical crest and cancellous bone,

Maximum principal strain in components,

Total strain energy partitioning (implant vs bone),

Interface micromotion/contact work.

4.3 Abutment material as a “system-level” composite choice

Not all composite strategies require a fully composite fixture. A 2024 FEA comparing titanium vs PEEK abutments shows that abutment material selection can affect stress distribution in the implant prosthetic system and surrounding bone.

Energy-wise, this is a controllable lever: you can shift part of the compliance/damping into the abutment while keeping a conventional titanium fixture, potentially balancing osseointegration confidence and load-transfer tuning.

4.4 Interface integrity, partial osseointegration, and debonding

Composite designs that increase compliance may raise micromotion at early stages if osseointegration is incomplete. Thus, realistic osseointegration assumptions are crucial. Debonding-aware contact formulations provide a pathway to model partially integrated interfaces and their evolution under load.

4.5 Recommended “Results” package for a composite dental implant paper

To make the composite effect explicit and reproducible, report:

SED maps (cortical crest + cancellous): baseline titanium vs composite(s).

Energy partitioning: 𝑈implant, 𝑈cortical, 𝑈cancellous under axial/oblique loading.

Component safety: max von Mises + max principal strain (abutment, screw, neck region).

Interface stability: micromotion/contact slip, plus sensitivity to osseointegration level.

Architecture sensitivity (if CFR-PEEK): short-fiber vs continuous-fiber comparisons.

5. Conclusions

Energy-based modeling helps translate “composite material choice” into a mechanistic narrative: composites primarily act by tuning stiffness and anisotropy, thereby re-routing strain energy and SED between implant components and peri-implant bone. Evidence across FE studies indicates that PEEK/CFR-PEEK and Ti–PEEK concepts can meaningfully change bone stress/SED patterns, but the benefits depend on reinforcement architecture and are accompanied by trade-offs—particularly increased strains and potential fatigue sensitivity in compliant systems under oblique loading.

A robust composite implant manuscript should therefore couple stress metrics with SED/energy partitioning, interface stability measures, and sensitivity analyses for bone quality and osseointegration level.